PRÉDIO

1 / 14

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution allows people to occupy abandoned properties that don't fulfill any social function. These buildings are informally referred to as 'Squats.' The Marconi has been occupied since 2012 and is still waiting to be deemed public housing (which would allow it to receive subsidies from the state). Roughly 400 people live in the building. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution allows people to occupy abandoned properties that...

READ ON

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution allows people to occupy abandoned properties that don't fulfill any social function. These buildings are informally referred to as 'Squats.' The Marconi has been occupied since 2012 and is still waiting to be deemed public housing (which would allow it to receive subsidies from the state). Roughly 400 people live in the building. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

2 / 14

Former offices, many of the rooms inside the Marconi have been adapted into studio apartments and are used by families who would otherwise be at risk of living on the streets. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

Former offices, many of the rooms inside the Marconi have been adapted into studio...

READ ON

Former offices, many of the rooms inside the Marconi have been adapted into studio apartments and are used by families who would otherwise be at risk of living on the streets. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

3 / 14

Portrait of Antonia, 56 years old, is one of the oldest and most respected women in the "Marconi" building. Originally from Paraíba, she came to São Paulo at eighteen and lived in the streets with a toddler. Later, she lived in a nun convent where she worked, forcing her to give up her baby for adoption. She explains: "Until now, I'm still asking her where my child is. And she keeps saying, "I don't know where your baby is." São Paulo, Brazil. 2016.

Portrait of Antonia, 56 years old, is one of the oldest and most respected women in the...

READ ON

Portrait of Antonia, 56 years old, is one of the oldest and most respected women in the "Marconi" building. Originally from Paraíba, she came to São Paulo at eighteen and lived in the streets with a toddler. Later, she lived in a nun convent where she worked, forcing her to give up her baby for adoption. She explains: "Until now, I'm still asking her where my child is. And she keeps saying, "I don't know where your baby is." São Paulo, Brazil. 2016.

4 / 14

A kid takes a photograph of his toys with a smartphone. Social groups shelter people who aren’t able to pay higher rent sums. São Paulo is the most populated city in South America, with over 30.000 people living in a homeless situation. São Paulo, Brazil. 2014.

A kid takes a photograph of his toys with a smartphone. Social groups shelter people who...

READ ON

A kid takes a photograph of his toys with a smartphone. Social groups shelter people who aren’t able to pay higher rent sums. São Paulo is the most populated city in South America, with over 30.000 people living in a homeless situation. São Paulo, Brazil. 2014.

5 / 14

William, 18 years old on the right, and Lenny, 24 years old. Families are often from the inland countryside as part of the internal migration of Brazil. ‘Squats’ are the only affordable solution for those who can’t survive with the minimum wage of 998 Brazilian reais per month (USD 262.25), when a standard rent costs about 1400 reais. São Paulo, Brazil. 2015.

William, 18 years old on the right, and Lenny, 24 years old. Families are often from the...

READ ON

William, 18 years old on the right, and Lenny, 24 years old. Families are often from the inland countryside as part of the internal migration of Brazil. ‘Squats’ are the only affordable solution for those who can’t survive with the minimum wage of 998 Brazilian reais per month (USD 262.25), when a standard rent costs about 1400 reais. São Paulo, Brazil. 2015.

6 / 14

Once a building is “squatted,” there are 72 hours where people must wait until police forces can not evict them. Essential services, like water, electricity, or sanitary sewers, are crafted and forced to function. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

Once a building is “squatted,” there are 72 hours where people must wait...

READ ON

Once a building is “squatted,” there are 72 hours where people must wait until police forces can not evict them. Essential services, like water, electricity, or sanitary sewers, are crafted and forced to function. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

7 / 14

Marco Antonio, 42 years old. After an extensive interview in his room, Marco Antonio falls asleep on his bed. Fatigue is a side effect of the medication he takes for schizophrenia and Asperger syndrome. São Paulo, Brazil. 2016. He explains in an interview: (...)Those are my pills…They aren't available in the Public Health Care system but are imported from the USA. I pay 100R$ (30 USD) for each dose...and sometimes I use two daily. (...)Dystonia, weakness, it's tough for me to get things done...I forget about things... that's why my room is such a mess, you know? But I think it is just because I'm always tired…And all of those boxes there are just junk(...). São Paulo, Brazil. 2016.

Marco Antonio, 42 years old. After an extensive interview in his room, Marco Antonio...

READ ON

Marco Antonio, 42 years old. After an extensive interview in his room, Marco Antonio falls asleep on his bed. Fatigue is a side effect of the medication he takes for schizophrenia and Asperger syndrome. São Paulo, Brazil. 2016. He explains in an interview: (...)Those are my pills…They aren't available in the Public Health Care system but are imported from the USA. I pay 100R$ (30 USD) for each dose...and sometimes I use two daily. (...)Dystonia, weakness, it's tough for me to get things done...I forget about things... that's why my room is such a mess, you know? But I think it is just because I'm always tired…And all of those boxes there are just junk(...). São Paulo, Brazil. 2016.

8 / 14

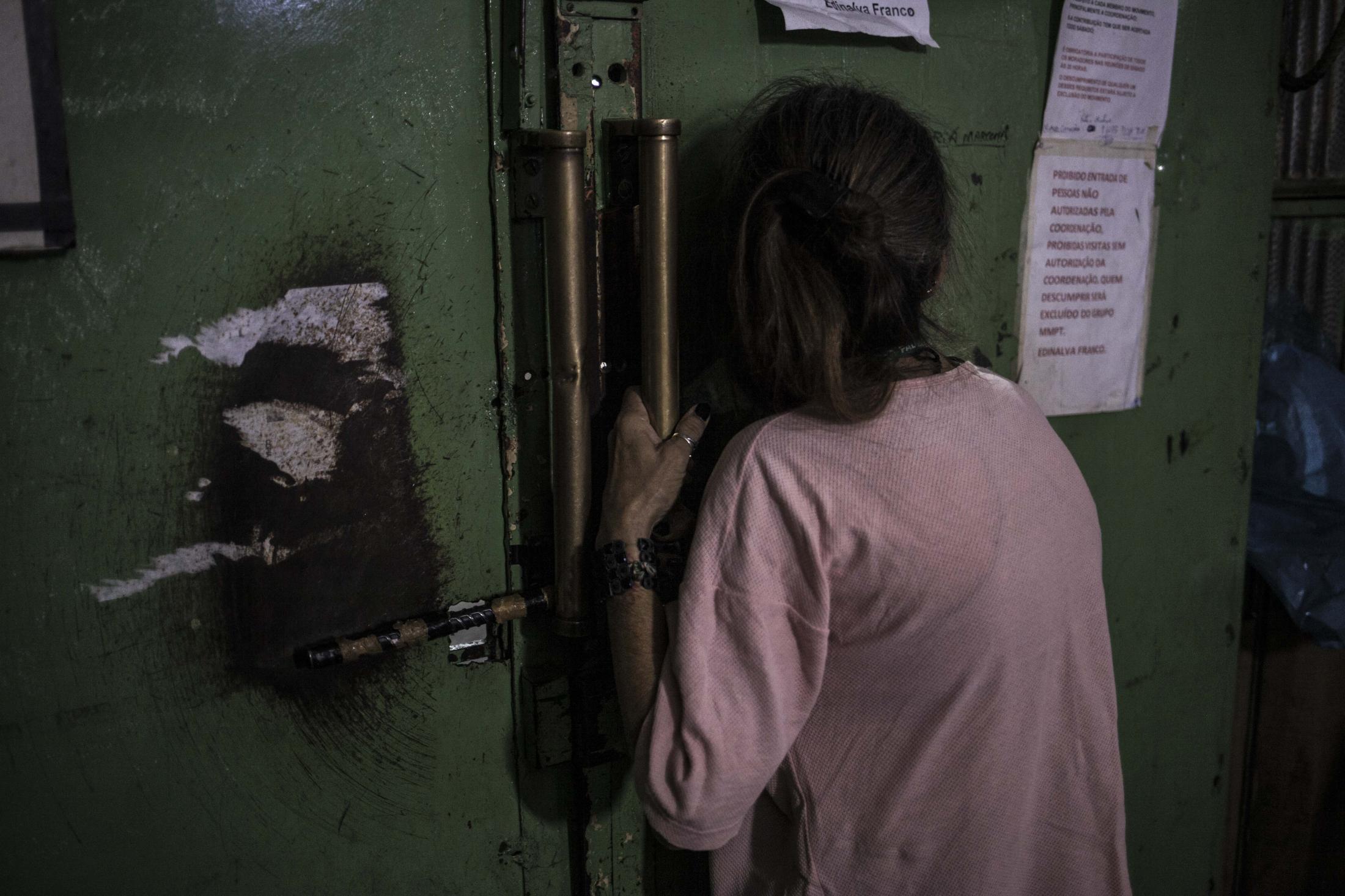

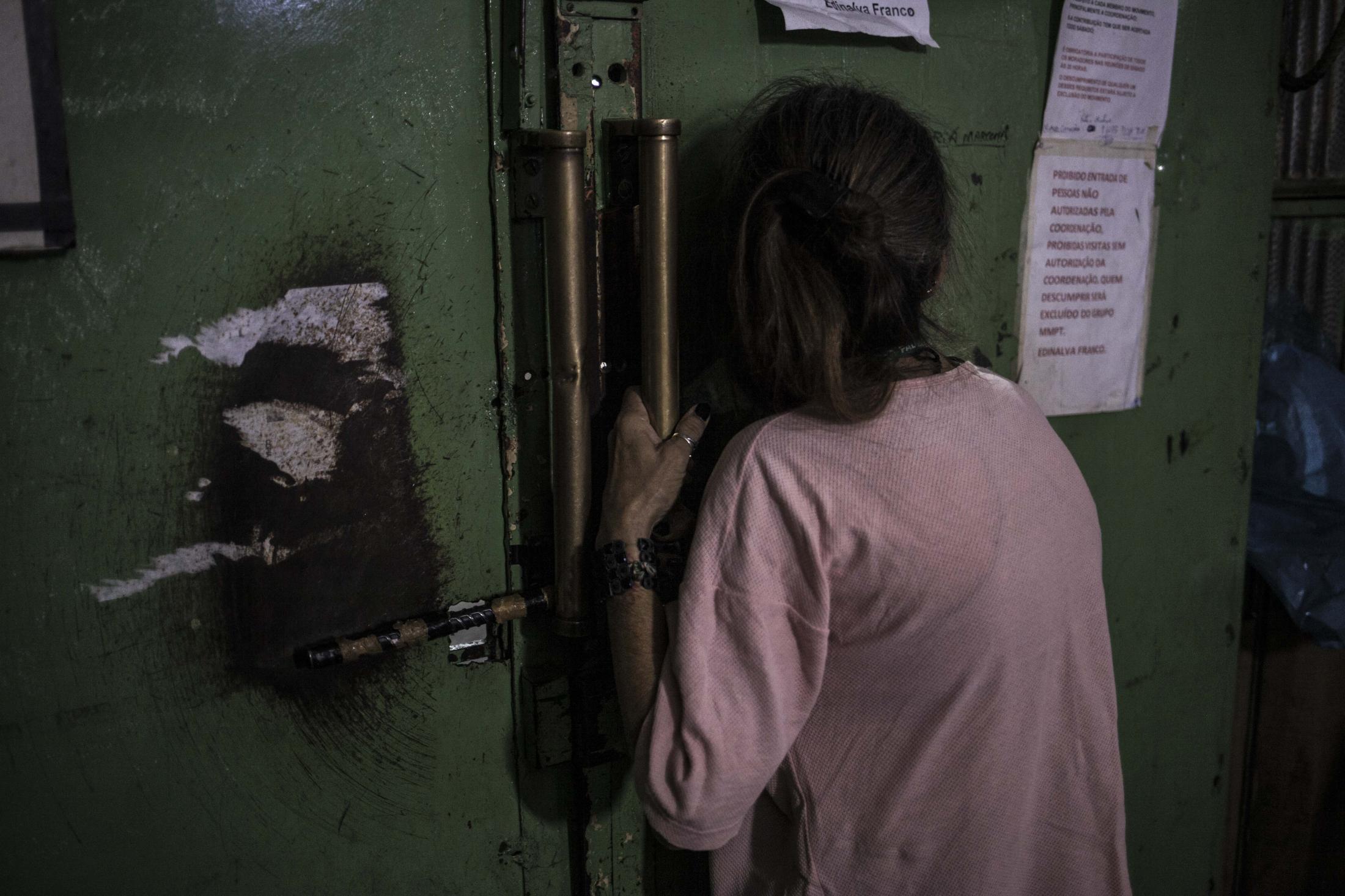

Kley was among the first people to claim the empty Marconi and began the process that she hopes will ultimately result in the building being recognized as public housing by the state. “This building is closed,” she says, explaining her thinking, “and we have so many people living in the streets.” São Paulo, 2014.

Kley was among the first people to claim the empty Marconi and began the process that she...

READ ON

Kley was among the first people to claim the empty Marconi and began the process that she hopes will ultimately result in the building being recognized as public housing by the state. “This building is closed,” she says, explaining her thinking, “and we have so many people living in the streets.” São Paulo, 2014.

9 / 14

A tent camp settled outside the ‘Palacio do Anhangabaú’ was another protest for housing resolutions. People stayed for over six weeks in improvised tents, sharing shifts and constantly cutting the transit to raise awareness and attention. São Paulo, Brazil. 2016.

A tent camp settled outside the ‘Palacio do Anhangabaú’ was another...

READ ON

A tent camp settled outside the ‘Palacio do Anhangabaú’ was another protest for housing resolutions. People stayed for over six weeks in improvised tents, sharing shifts and constantly cutting the transit to raise awareness and attention. São Paulo, Brazil. 2016.

10 / 14

Window view from the Marconi, looking at an office building in São Paulo’s downtown, where abandoned and active real estate blends into the urban landscape. São Paulo, Brazil. 2014.

Window view from the Marconi, looking at an office building in São Paulo’s...

READ ON

Window view from the Marconi, looking at an office building in São Paulo’s downtown, where abandoned and active real estate blends into the urban landscape. São Paulo, Brazil. 2014.

11 / 14

Families are often from the inland countryside as part of the internal migration of Brazil. ‘Squats’ are the only affordable solution for those who aren’t able to survive with the minimum wage of 998 Brazilian reais per month (USD 262.25). A standard rent costs about 1400 reais (USD 400). São Paulo, Brazil. 2015.

Families are often from the inland countryside as part of the internal migration of...

READ ON

Families are often from the inland countryside as part of the internal migration of Brazil. ‘Squats’ are the only affordable solution for those who aren’t able to survive with the minimum wage of 998 Brazilian reais per month (USD 262.25). A standard rent costs about 1400 reais (USD 400). São Paulo, Brazil. 2015.

12 / 14

A family of five with three kids and a dog sleeps in what was once a dentist’s office, now adapted into a 100 sq ft room. One of the movement's challenges was adapting spaces for pregnant women and newborn babies since the building hadn’t received any disease control or safety inspection. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

A family of five with three kids and a dog sleeps in what was once a dentist’s...

READ ON

A family of five with three kids and a dog sleeps in what was once a dentist’s office, now adapted into a 100 sq ft room. One of the movement's challenges was adapting spaces for pregnant women and newborn babies since the building hadn’t received any disease control or safety inspection. São Paulo, Brazil. 2018.

13 / 14

Despite the significant number of people in São Paulo who are living on the streets, the city is home to hundreds of uninhabited properties. These buildings often stand empty and abandoned when speculating with the city’s housing market. São Paulo, 2018.

Despite the significant number of people in São Paulo who are living on the...

READ ON

Despite the significant number of people in São Paulo who are living on the streets, the city is home to hundreds of uninhabited properties. These buildings often stand empty and abandoned when speculating with the city’s housing market. São Paulo, 2018.

On the 13 floors of the ‘Marconi’ squat, about 400 people are accommodated in offices adapted into rooms of 50 to 100 sq ft, under the uncertainty of a decent housing solution. Within it, the notion of home (a space of emotional relationships and identity) becomes as unstable as the memories and expectations of a steady future. Marconi is a place where life stories share nostalgia and experiences of loss.

Several life testimonies from the residents of Marconi invite us to ask ourselves how deep we can see within our cities. How do we deal with housing problems? Who organizes? Where is the real crime in all this? To whom is it visible, and who is not? ‘PREDIO encourages dialogue about an urban crisis within a South American historical context and what we leave behind in our identity and collective memory.

The whole body of work consists of photographs, video interviews, archival material, and collages from a personal travel journal.

In 2022, “PREDIO” was acquired by the National Center for Contemporary Arts (CHILE) to be included in its permanent collection. Ediciones Buen Lugar published the book, making the title a finalist in the Lucie Foundation Book Prize for the “First Book" category, finalist for FELIFA 2023 photobook award, and first prize for the Latin American Design Awards for best editorial design.